The PAH heart and lung connection

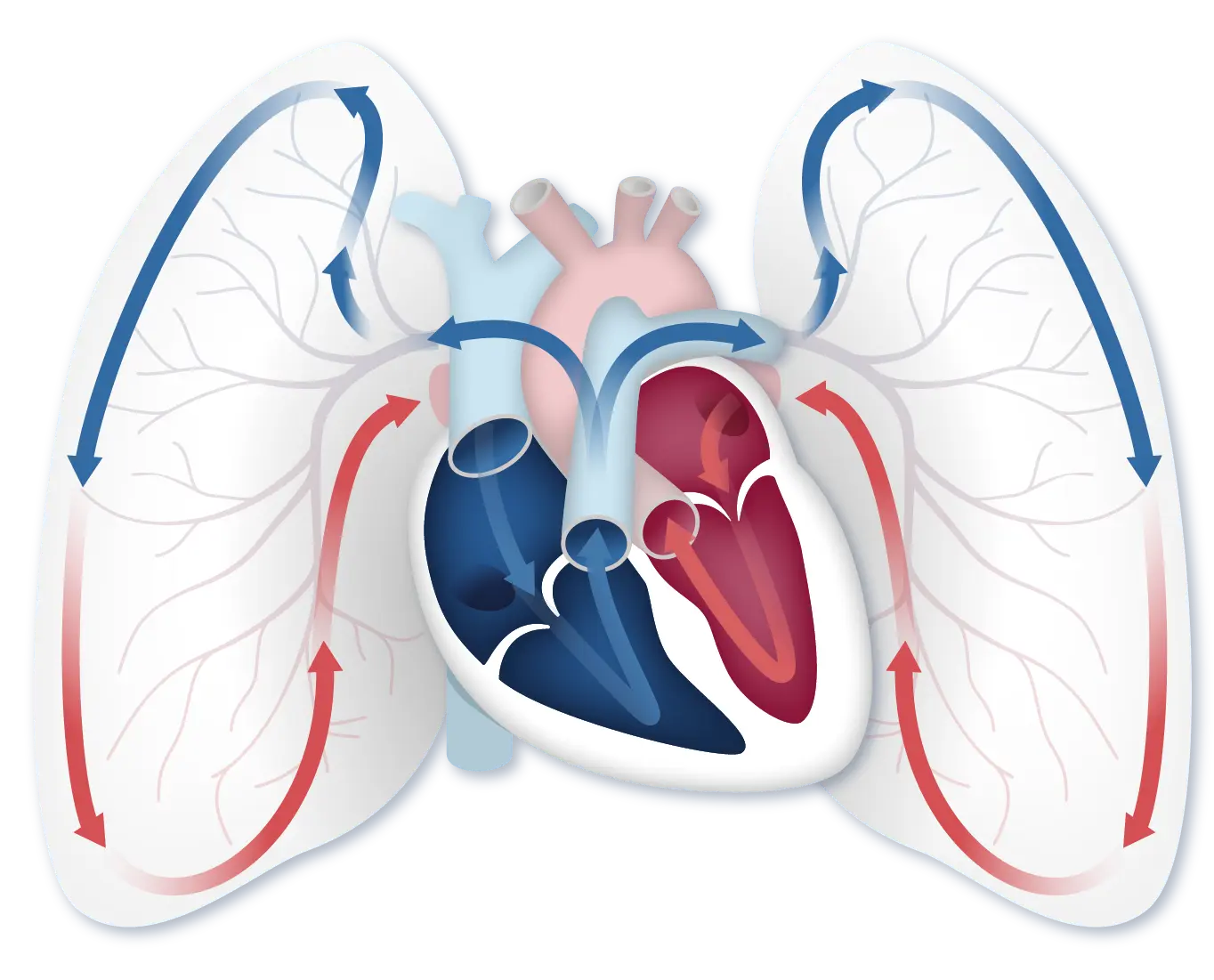

Your heart and lungs work together to make sure that your body gets the oxygen it needs. Knowing how the heart and lungs work together as partners will help you understand what happens in your body when you have pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

When you inhale, you breathe oxygen into your lungs. Blood flows from the heart to the lungs, where it picks up oxygen. The oxygenated blood goes back into the heart, where it is pushed out to the rest of the body.

When you have PAH, the blood vessels in your lungs thicken and become narrow, making the right side of your heart work harder to pump blood through them. This can cause serious, life-threatening changes to the right side of the heart and can even cause heart failure.

A closer look at the heart

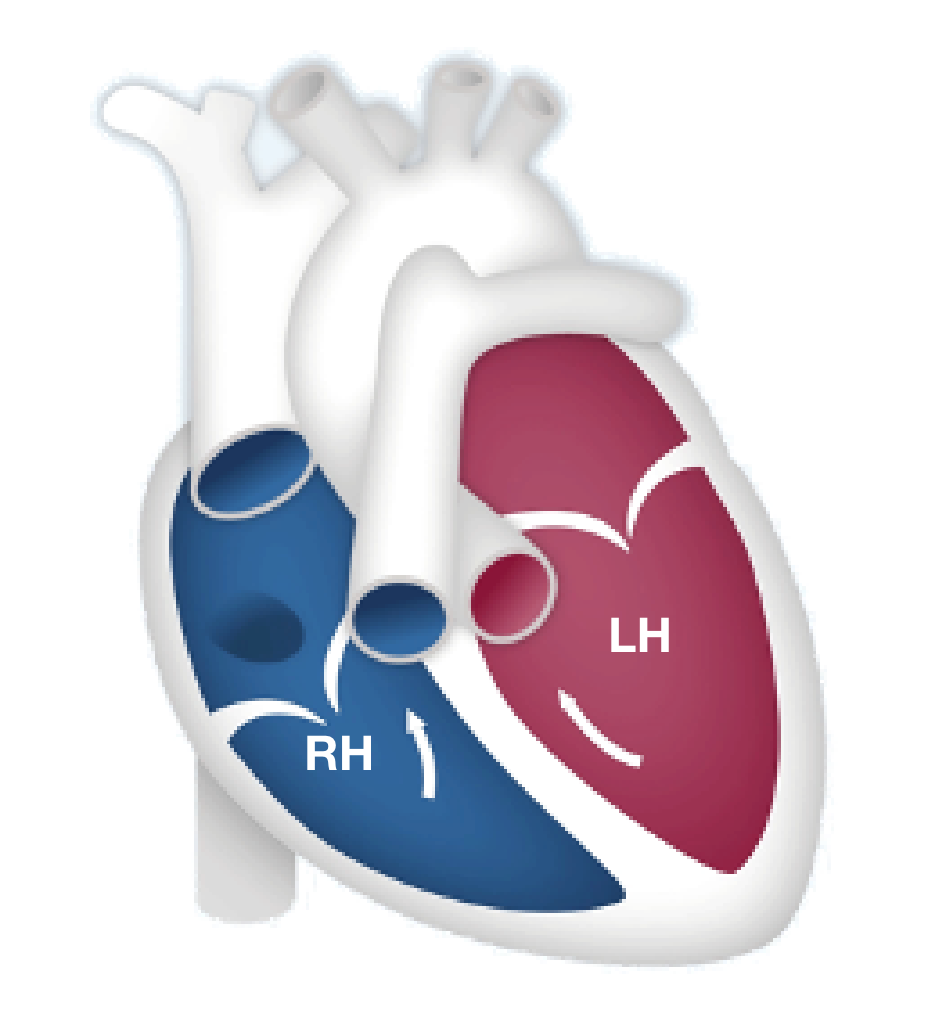

Each side of the heart has a specific job when it comes to getting your body the oxygen that it needs. Each side is built differently to best perform its job.

The right side of the heart is smaller and thinner because it is only meant to push the blood a short distance—from the heart to the lungs—to receive oxygen. The right side of the heart pumps blood into the blood vessels in your lungs. As blood flows through the lungs in these small vessels, red blood cells pick up oxygen from the air we breathe.

After the blood has received oxygen, it travels to the left side of the heart, which pumps that blood out to the rest of the body. The left side of the heart is larger and stronger than the right side because it has to push this oxygenated blood a long distance throughout the entire body.

PAH affects the right side of the heart

Now that we know a little more about how the heart and lungs work together, let’s talk about PAH.

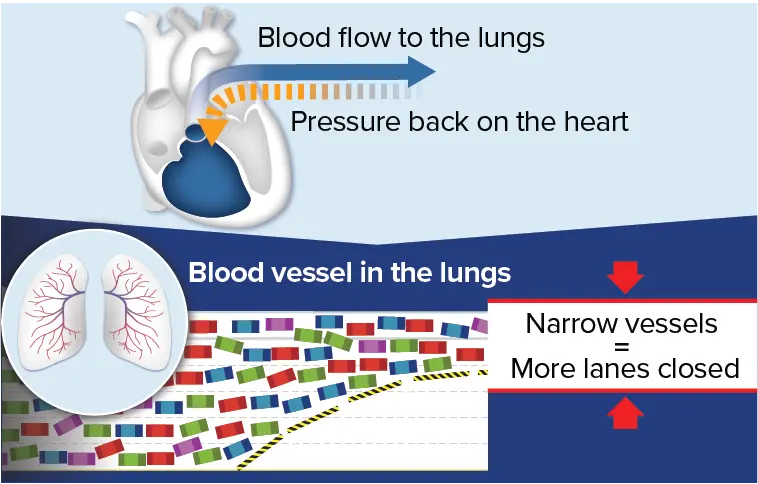

PAH, a lung disease, is a specific type of high blood pressure that affects your heart and lungs. PAH begins when the walls of the lung’s blood vessels thicken and narrow. When this happens, it becomes harder for blood to pass through the vessels, and that means there is less blood flowing to the lungs. The reduced blood flow in the lungs creates pressure on the right side of the heart.

PAH can be confusing

This video explains the basics of PAH and how it affects the body. You’ll learn how PAH changes the heart and lungs, what happens as PAH progresses, and symptoms of PAH progression.

[Video title: PAH Basics, Part 1 in the PAH Initiative Video Series] Hi, I’m Dr Lana Melendres-Groves, a pulmonary arterial hypertension specialist and director of the pulmonary hypertension program at the University of New Mexico. I have been treating pulmonary diseases for over 12 years with a specialization in PAH for over 9 years. My clinic has treated over 5,000 patients and I currently oversee 250 PAH patients on PAH-specific medicines. In this video, we’ll cover the basics of pulmonary arterial hypertension, also known as PAH. Understanding what PAH is can be confusing because even healthcare providers may tell you different things about it. Some may say your heart doesn’t work as well as it needs to. It’s really about the blood vessels. The real problem is in the lungs or it’s just hypertension. This is why it’s so important to find an experienced PAH specialist to help you. A PAH specialist is a cardiologist or pulmonologist who has had specific training in PAH and understands how challenging this disease really is.

The heart, lungs, and blood vessels all work together as a cardiovascular team and PAH affects each of these vital organs. So let’s start with the heart. You may already know that the heart has 4 chambers. Two chambers are called atria and receive blood from the other parts of the body and the other 2 chambers are called ventricles and pump blood out of the heart. The right atrium receives blue, oxygen-poor blood from the body and the right ventricle pumps that oxygen-poor blood to the lungs where it can pick up oxygen. The left atrium receives red, oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and then the left ventricle pumps the oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. Although cardiac diseases, including heart attacks, are more common in the left ventricle, it’s actually the right ventricle that is affected in people who have PAH.

[End of video: PAH Initiative, Sponsored by United Therapeutics, Committed to Improving the Lives of Patients. For more resources about PAH, please visit www.PAHInitiative.com. Copyright 2019 United Therapeutics Corporation. All rights reserved.]

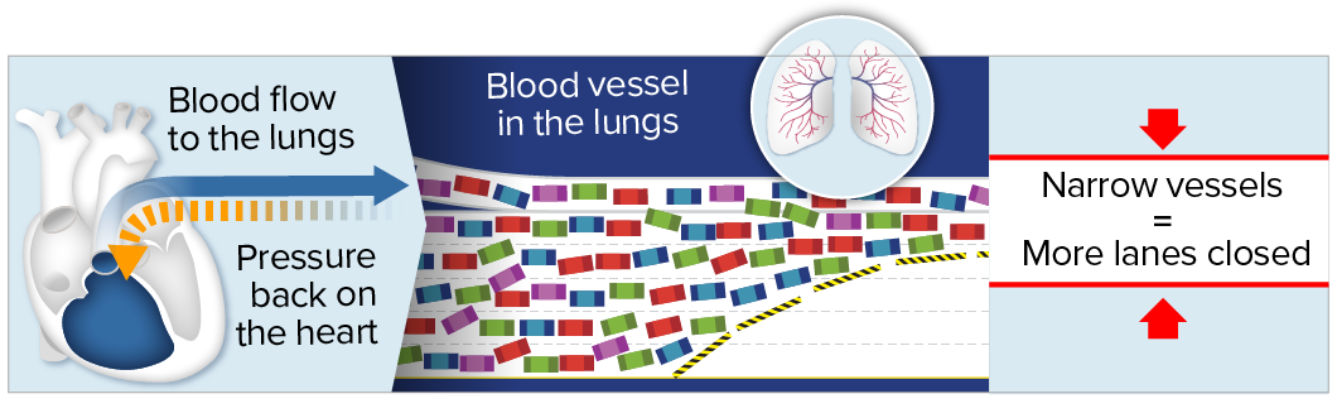

Think of PAH like construction on a highway

Imagine your blood vessels as the highway. Your blood cells are like the cars. When blood vessels in the lungs become narrow, the flow of blood cells is reduced—similar to the way traffic flow slows down when lanes are closed.

With PAH, the heart works harder

When blood vessels in the lungs narrow, the heart has to work harder to pump blood through the lungs to receive enough oxygen to be carried throughout the body.

The right side of the heart grows larger and more muscular as it pumps harder. This may sound like a good thing but remember, the right side of the heart is not meant to work hard. It’s only meant to pump blood from the heart to the lungs. When it has to pump harder for a long period of time, the right side of the heart becomes damaged.

When the right side of the heart struggles to keep up, the rest of your body doesn’t get the oxygen it needs to function. This is when PAH symptoms often get worse.

With PAH, narrowed blood vessels in the lungs cause blood flow to slow down and back up, similarly to traffic during construction on a highway. This backup creates pressure, which strains the heart over time.

With PAH, narrowed blood vessels in the lungs cause blood flow to slow down and back up, similarly to traffic during construction on a highway. This backup creates pressure, which strains the heart over time.Opening the blood vessels in the lungs reduces pressure on the heart

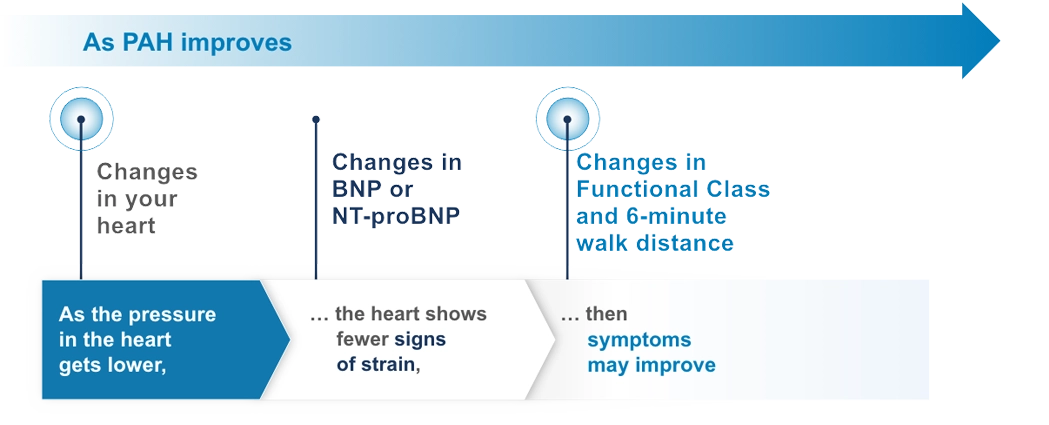

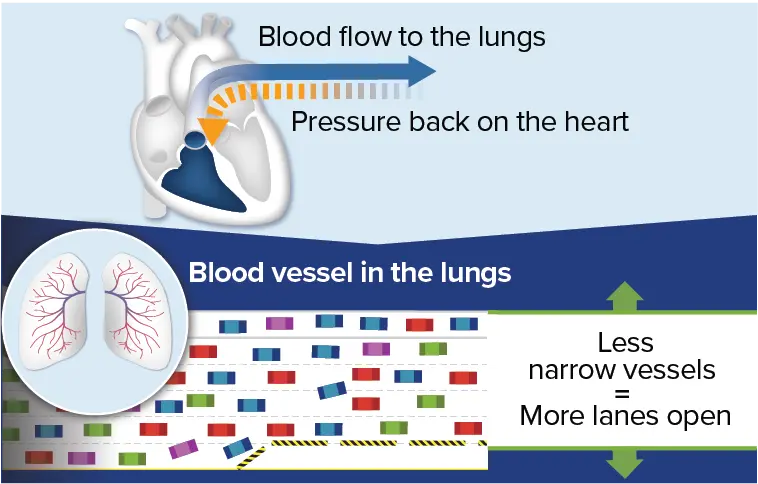

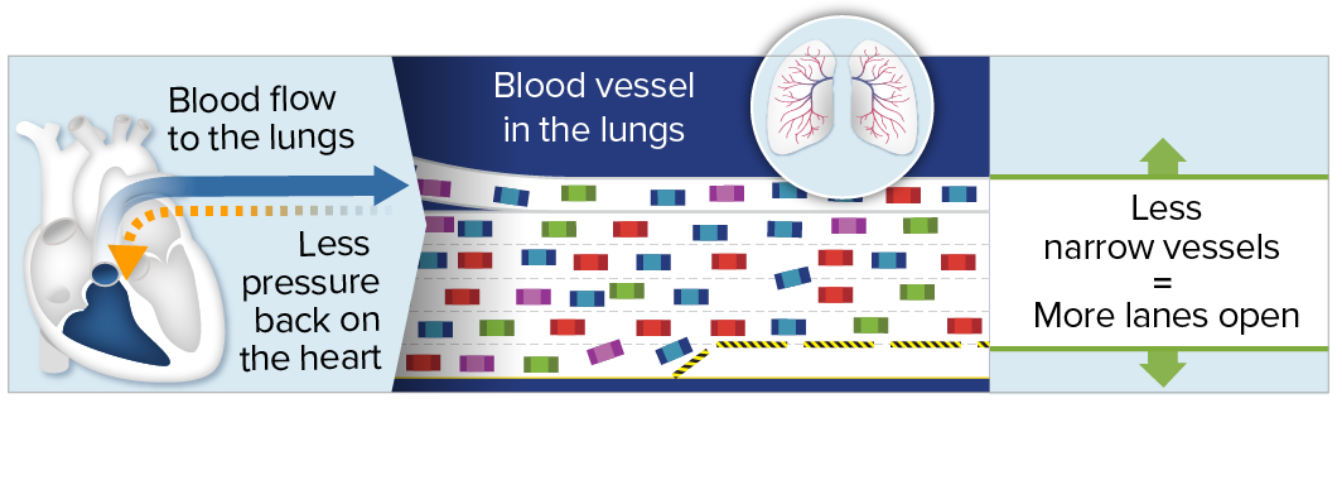

PAH medications help to open up the “lanes” by giving the blood more space to flow through (for example, by making the blood vessels wider). Wider lanes help traffic (blood cells) move faster and more smoothly, with less backup. This means that the heart doesn’t have to work as hard to pump the same amount of blood through the lungs, and more oxygen can get to the rest of the body.

An important goal of treating PAH is to help the vessels in the lungs widen to improve blood flow, similarly to how traffic moves faster when more lanes are open. Because the blood flows more smoothly, there is less pressure and strain on the heart. Over time, with less strain on the heart, symptoms may also improve.

An important goal of treating PAH is to help the vessels in the lungs widen to improve blood flow, similarly to how traffic moves faster when more lanes are open. Because the blood flows more smoothly, there is less pressure and strain on the heart. Over time, with less strain on the heart, symptoms may also improve.What can monitoring the heart tell healthcare providers?

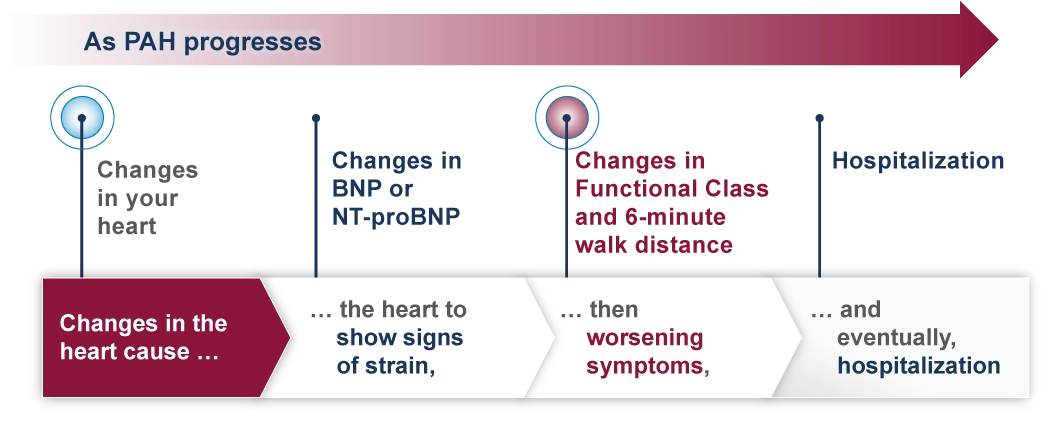

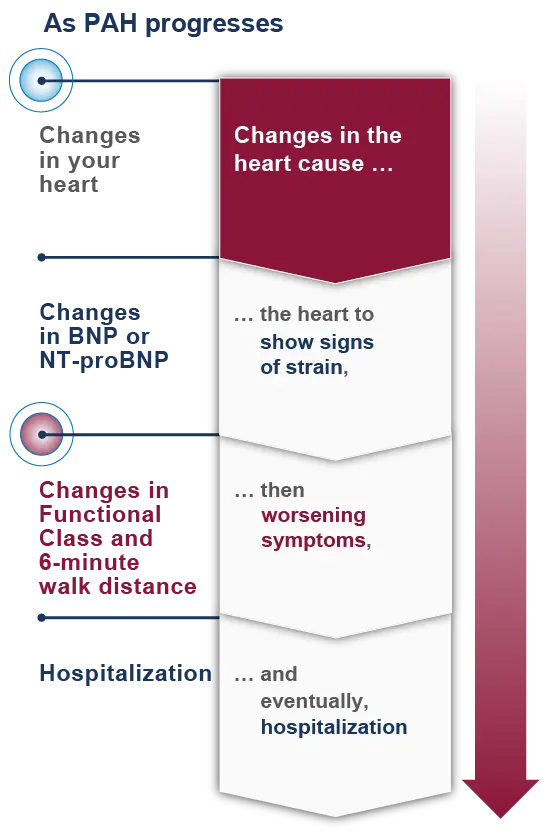

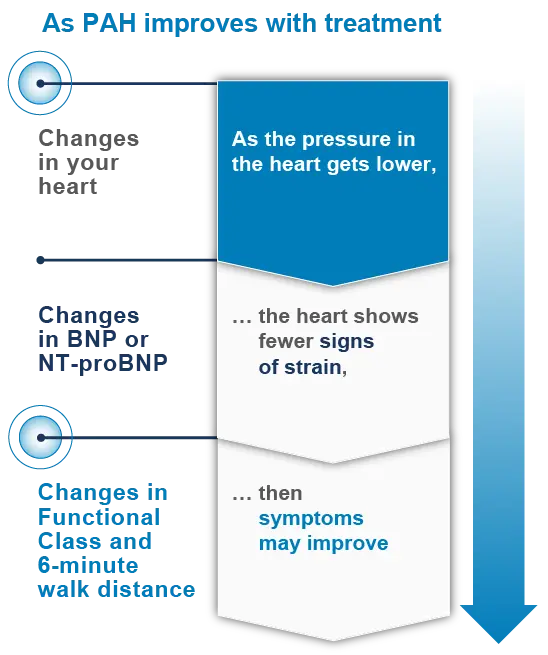

Changes in the heart can be an early sign that PAH is getting better or worse. This is because changes to your heart occur before your symptoms, including your Functional Class or 6-minute walk distance.

Because of this, changes in the heart can be an early signal to healthcare providers that treatment plan adjustments—such as PAH medications and lifestyle (diet and exercise) modifications—may be beneficial. Changes in the heart can also be an early signal that your treatment plan is working.

Changes in your heart occur before your symptoms change

Changes to the heart occur before changes to biomarkers that can be monitored with blood tests (BNP or NT-proBNP levels). Changes to biomarkers in your blood occur before changes in Functional Class and 6-minute walk distance, and changes in Functional Class and 6-minute walk distance occur before hospitalization.

Echocardiograms can monitor how the heart is changing

PAH specialists now understand how important it is to monitor the right side of the heart frequently. An echocardiogram (Echo) can be used to catch any changes early and also to see how you are responding to your treatment plan. This is why Echos are so important.

How often should I get an Echo?

Echos are recommended at least twice a year for many patients with PAH.

Echo: Getting to the heart of the matter

Take a look at how PAH specialists use the Echo as a noninvasive test to monitor changes in the right heart. Learn more about how the results from your Echo can help guide you and your doctor to take action.

PAH Today: Echo – Getting to the Heart of the Matter

Lana Melendres-Groves, MD:

[on-screen text: Lana Melendres-Groves, MD, Medical Director, Pulmonary Hypertension Program] Welcome to the PAH Today National Broadcast Series. My name is Dr. Lana Melendres-Groves, and I’m the Medical Director for the Pulmonary Hypertension Program at the University of New Mexico. In today’s broadcast, we’re going to be talking about echocardiogram, or Echo: Getting to the Heart of the Matter. Before we do, I just wanted to say thank you to all of you for joining us, whether this is your first time joining, or if you’ve been with us through all three broadcasts, it is amazing, and I applaud you for all of the work that you’re doing to learn more about your disease, PAH. Today, we want to take a little bit closer look at the Echo, something that many of you may have had one or many of throughout your process, and throughout all of the providers that you may have seen.

Before we get to that, I would like to give the following disclaimer. “This presentation is sponsored by and made on behalf of United Therapeutics. Healthcare professional speakers are compensated by UT. Not all drugs are appropriate for all patients. Speak with your healthcare professional to determine which treatment plan is right for you.”

All right, so in today’s presentation, it’s broken down into three parts. The first is going to be talking about the heart in PAH. Then we’ll move into a deeper dive about the echocardiogram, and then we’ll start talking about ways to learn more and continue that learning.

All right, so let’s get to this first section, talking about the heart in PAH. Now whether you have joined us for all three of our broadcasts, or this is your first time, what I’d like to do is provide a bit of a recap as to what we have talked about in the prior broadcast, which was discussing really what PAH is and how it may affect the heart. In this situation, what we’re looking at in terms of pulmonary arterial hypertension is that those blood vessels that carry blood from the right side of the heart into the lungs begin to become more narrowed. As those blood vessels narrow, it becomes more difficult for the heart on the right side to pump blood into the lungs. This causes the heart to eventually grow larger and weaker, and over time, then we start to see these changes.

Now, one of the things that tends to be the first thing that changes is going to be how the heart appears. Many times, it might be very difficult to even think about how we see that. Then this is where the Echo comes into play, which we’ll get into a little bit later. Why it’s so important to understand about those changes in the heart, is that it kind of predicts what may be to come. For instance, as the heart begins to weaken, we may see increases in some of the blood tests that we get, what we call biomarkers, such as BNP or NT-proBNP. These are lab tests that help to say, how’s the heart feeling? Is it feeling strained or stretched? Then we start to see our patients beginning to have changes in how they do and how they feel. For instance, when we ask our patients to perform a six-minute walk test, we may find that that distance starts to become less and less, or that their symptoms become greater, such as shortness of breath or fatigue, and eventually, all of these changes may lead to our patients becoming hospitalized.

So how can we monitor for those changes before all of the rest of what we just talked about occurs? We have a couple of different methods that we use. One of them is considered noninvasive, and that is the echocardiogram. As I mentioned, we like to call it an Echo for short. And then the second is through a right heart catheterization. This, if you had a definitive diagnosis of PAH, is something that I’m sure you haven’t forgotten. It’s where we go through the blood vessel, either in the arm, the neck, or the leg in order to find out how the heart is doing from inside those chambers of the heart and the blood vessels in the lungs.

Let me talk just a little bit more about that right heart catheterization and the measurements that we obtain from it. What we’re looking for are specifically and directly measuring the pressure within the heart and then within the blood vessels of the lungs, but we’re also able to better understand how well the heart is pumping that blood. We call this the cardiac output, just meaning, how much blood does the heart squeeze every time that it’s squeezing to send blood into those blood vessels?

[on-screen text: These measurements are used to diagnose PAH, monitor response to treatment, and monitor disease status.] So often, these measurements are used for different things. The first is, we need the right heart catheterization in order to diagnose PAH. But then, we may ask you to get another one, and I know that my patients are never looking forward to that, but the reason that we request it is because, in terms of evaluation and monitoring of our patients, these invasive measurements through right heart catheterization may give us information on how our patient is doing after we’ve changed a treatment, or maybe their symptoms have changed, and this gives us a better idea as to whether it’s related to PAH, or maybe to something different.

These measurements become so important, because as I talked about a little bit earlier, we look at those narrowing blood vessels within the lungs. As those blood vessels narrow, they have an increased resistance in terms of getting blood through them. We call that pulmonary vascular resistance, or PVR. This is just, how hard does the heart have to work to overcome the resistance of those narrowed blood vessels. We also measure the mean pulmonary artery pressure within the blood vessels. This gives us an idea of how much pressure the heart has to generate to get blood through those narrow blood vessels. We also measure the pressure within the right atrium. That’s the first and smaller chamber on the right side of the heart. This helps us often in terms of the prognosis for our patients. All of these measurements require the invasive test of a right heart catheterization.

So, we don’t necessarily want to put our patients through an invasive test every time we’re trying to understand how they’re doing or how their heart may look. In this situation, we ask our patients to obtain an Echo. This is a noninvasive way to monitor for changes in the heart. For instance, it may give us an idea of whether the heart is becoming more enlarged, or if we’re starting to see progress in terms of the therapies our patients are on, and we’re seeing more normalization of the heart.

The way that the Echo does this is it uses soundwaves, or ultrasound to create pictures of the heart. This is the most widely used tool for assessing the structure and function of the heart. We really use it as our screening tool.

So, what does it actually tell us as a healthcare provider? Well, it helps me to understand how my patient’s diagnosis of PAH is affecting their heart. It also gives me an indication of what the current treatments are doing to either improve, or maybe we’ve not gotten it improved enough. And then, once we have changed a regimen or started a regimen of treatments for our patients, we’re able to follow for potential improvement in how the heart looks, how it works, the sizes of the chambers, and all of those things may change over time.

So that brings us to the next section, taking a bit of a deeper dive into the Echo, not just on the surface of why we get it, but what these pictures actually mean and actually look like sometimes.

So, when we talk about an echocardiogram, what we’re looking at are all of the different chambers in the heart. So, we have four muscle chambers. We have two chambers on the right side of the heart that are depicted in blue, and we have the two chambers on the left side of the heart depicted in red. I also break it down into the two smaller chambers, which are sort of on the top of the heart, called the right and left atrium, or the two larger chambers that sit below those small chambers called the right ventricle and left ventricle. With the Echo, we’re able to look at the size of the chambers of the heart, we’re able to tell by the shape of them and how they squeeze and the thickness of the muscles how the heart may be doing overall and how it’s functioning. This can change with therapies, and so therefore, we can use it as an evaluation to a response to a therapy.

So, let’s go ahead and look at an Echo. Well first, we have to let you know that we actually flip the heart upside down when we look at it, so we took the picture from the prior slide and flipped it upside down. So, this is how we really look at it when we look at an Echocardiogram. It’s flipped upside down, so now those larger chambers, the ventricles, are sitting toward the top, as you can see, and those smaller chambers are sitting toward the bottom of the screen. Now I know, it’s a lot of kind of black, white, and gray, so hopefully you’re able to sort of see that within those white areas are the chambers of the heart, and the black area is where the blood would be moving through. You can see that the arrows show the distance between the walls of the right ventricle and the left ventricle, and you may note that the right ventricle is smaller than the left ventricle, and that is completely normal for a patient who does not have PAH.

We also look at what we call the apex of the right ventricle. So, it’s kind of the point of it, and it usually is very thin-walled, and because the right side of the heart is under low pressures in a normal situation, the walls of the muscle don’t have to be thickened. We also can see that the right atrium and left atrium are about the same size. This, again, is in a person who does not have PAH.

So, what happens to the heart in a patient with PAH? Well, let’s go ahead and take a look at a side by side of a patient with an advanced or severe pulmonary arterial hypertension, PAH, and then somebody who does not have PAH. You can see that they look pretty dramatically different. You can note that the area of the right ventricle of the patient without PAH starts to become much more enlarged when somebody has advancing PAH. You can also see that the left ventricle seems to be shrinking in size. Well, it’s not technically shrinking, it’s just being kind of pushed over because the right ventricle and the left ventricle share that middle wall, so as the right ventricle starts to enlarge, it pushes into the wall, kind of squishes the left side of the heart. You may also notice that the right atrium has become substantially enlarged, especially compared to the left atrium. There are many other aspects that we also look at when determining how advanced someone’s PAH is that we won’t go into today, but again, are things that you may feel interested in and want to learn further about.

So, in this situation, what we look for is a patient with PAH having a right ventricle that is larger than normal. We also look for thickening of the muscle at that point or apex of the right ventricle, and we tend to see that the right atrium is enlarged.

[on-screen text: Monitoring the right heart with Echo helps healthcare providers be proactive with treatment and try to prevent symptoms before they happen. Symptoms worsen after changes in the heart occur.] So again, coming back to this graph, those changes in the heart help us to proactively understand what might be coming from a clinical side of it, meaning how you feel and what you’re able to do. And so, instead of waiting until someone feels those symptoms, we can use an echocardiogram to act more urgently on their behalf. We don’t ever want to see our patients’ symptoms worsen to the point that they may require hospitalization.

The Echo also becomes an important part of assessing risk status. We’ve talked about risk status in some of our prior broadcasts, and I think it’s important to bring it up now as well, and whether this is the first time you’re seeing this chart, or this is something that you’ve become well versed with, I do want to highlight the aspect of it that includes the Echo, which is in the blue box. We really do look at the size of the right atrium and whether there’s fluid around the heart called a pericardial effusion to help determine prognostically how somebody is doing and may place them in a low-, intermediate-, or high-risk status. It’s essential that risk assessments are done at least every 3 to 6 months. In terms of the echocardiogram, your provider may choose to get it as frequently as that or less often based off your needs. Overall, our PAH treatment guidelines indicate that our goal is to reach a low-risk status, and that for our patients, that long term, this will improve their ability to do more and live longer. It’s now my pleasure to be able to introduce Dr. Anjali Vaidya who is a dear friend of mine and a colleague. She also happens to be a cardiologist, which will help bring in a different perspective in terms of the Echo. Well, Anjali, I’m so excited that you’re here. I know that we’ve really created a wonderful friendship within the PAH space, and you’ve taught me so much when it comes to Echos and the perspective of a cardiologist, and I’m hopeful that, before we get into all of that with our audience, that you might be able to just give us a bit of a background and introduction of yourself.

Anjali Vaidya, MD, FACC, FASE, FACP:

Yes, happy to. Thank you so much, Lana, for having me, and for all of your efforts and great work in pulmonary hypertension and education. I am a cardiologist, and I think you and I have always enjoyed the work we’ve done together because of the important balance between cardiology and pulmonary expertise. And so, my background is, I’m an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist trained in echocardiography, as well as pulmonary hypertension. My entire practice now is fully dedicated to all forms of pulmonary hypertension, so I’m based out of Philadelphia, and I serve as the co-director of the pulmonary hypertension right heart failure and CTEPH program at Temple University, where I also serve as part of the cardiology fellowship as well as our internal medicine residency program, so a big passion of mine is education in medicine in general, and of course, with emphasis toward all aspects of pulmonary hypertension.

Lana Melendres-Groves, MD:

Well, the good news is that you clearly don’t have anything that you have to do, and you’re never busy based off of that. But, we do really appreciate that you took some time out of your day to be able to talk a bit about Echos because I know that from the perspective of pulmonologists, there are certain things that I definitely look at, but I’d really like to understand a bit better how you use Echos in your practice.

Anjali Vaidya, MD, FACC, FASE, FACP:

Absolutely. Echocardiography, to me in pulmonary hypertension, is the most informative and highest yield test of everything that we do. It sort of ranges from the initial recognition of pulmonary hypertension to identify that a patient who’s struggling with trouble breathing or chest pain or feeling dizzy or lightheaded or fluid buildup before the even have a diagnosis, the Echo is really the most important test to recognize that they have pulmonary hypertension, and then I would say we take it many steps beyond that after the diagnosis is made and confirmed, in looking at the Echo throughout the duration of the patient’s life as we take care of them for years and years and years, because it’s usually the first clue that something is changing or that their treatment is working and that they’re exactly where we want them to be at goal. And so, we use them frequently, it’s a noninvasive, relatively pain-free, quick procedure to have done, ultrasound of the heart. We do them every time we change a medication for pulmonary hypertension to get a closer look at the heart to see, okay, how’s the pulmonary hypertension responding. We’ll do surveillance every six months, once a year, to make sure that patients are still at goal, and it’s a really informative way to know if we need to escalate the therapy for our patients.

Lana Melendres-Groves, MD:

And I think today, what the goal of this broadcast is, is really to help inform patients to better understand this test that we’re always asking them to get. And let’s be honest, they’re in there with a technician, and they can see it on the screen frequently, and they really are trying to understand why we’re doing this and what all the black, white, and gray on the screen means. So, are there specific things that you actually talk to your patient about in terms of what you see on the Echo, not that you necessarily show them their Echo, but just some of those findings?

Anjali Vaidya, MD, FACC, FASE, FACP:

Absolutely. I would say, in the very beginning of their diagnosis, there’s a lot of emphasis on the pressure estimation, which can be done on the echocardiogram. I always tell my patients that pressure estimation is an initial sign to say, hey, look closer, there’s something wrong, we need to sort this out further. And then, although it might sound a little counterintutitive, that pressure estimation, that number that the echocardiogram gives, actually after the diagnosis is made, is actually sort of the least important detail that we hone in on. And so the reason I say that is because we’ve learned over many, many years of really good research that’s been done, certainly at our institution, but around the country and around the world, that the specific parameters and the details of how the right side of the heart is performing, are the factors that directly correlate with a patient’s prognosis and their survival and their risk for being in the hospital and how they feel. And so, with that in mind, Lana, to answer your question, when I’m looking at those Echos of my patients on medicine, over time, I’m paying most close attention to the right ventricle, which is the main pumping chamber on the right side of the heart, and looking at the function, is it normal? The goal of the treatment for pulmonary hypertension is to normalize the function of the right side of the heart, and when patients are first diagnosed, often their function is very poor, and so the goal is, does the right side of the heart function look normal, but I’m also looking at other parameters that correlate with, not just the function, but the structure and the shape of the right side of the heart, which go along with how much work the right side of the heart has to do. That stiffness in the pulmonary arteries, and the work and the load and the weight, so to speak, that that muscle of the right side of the heart has to lift, I can see those impacts based on not just the function, but also the shape and structure of the right side of the heart.

Lana Melendres-Groves, MD:

And I love that you brought up that pressure that is often reported on the readout that somebody may be able to access through their medical records. Because it’s not something we talked about actually today, and I think it’s something that often people and other physicians may be more fixated on, so it’s really wonderful to hear that, when it comes to understanding how someone’s doing, that that really takes a back seat to all of those other structural changes that we may see. I would say that, when I talk to my patients about the Echo, I do a very similar thing: we talk about whether the right side, the right ventricle is enlarged, and to potentially what degree, and after we’ve started therapies, seeing that maybe it’s remodeled, or that it’s starting to change and become more normal, so I think that that’s extremely important. One of the things you talked about a little bit earlier was that you tend to get Echos for sort of surveillance, or when you’re changing medications, and so would you say that there’s any set in stone time frame that these patients get their Echos, or is it really based off of everybody’s individual needs?

Anjali Vaidya, MD, FACC, FASE, FACP:

Yeah, that’s a great question, and I think the answer to that has probably evolved in the time, even in the time that you and I have been taking care of these patients. And by the way, I really like that you said you didn’t spend much time talking about the pressure estimation in the conversation earlier, because that really shows how up-to-date and modern and sort of progressive your teaching is. And it’s hard to do that when the temptation from us and our patients is, hey, what does the pressure show, what does the pressure show, I think it takes a lot of insight and wherewithal to shift the conversation away from that into the modern era of what we know is more important. I think that’s great. I would say it really is an individual kind of assessment on how frequently I’m reassessing the echocardiogram, and I’ll frame it in the context of sort of the whole patient and the reason why it can vary, because our goal for the patient is for them to feel well and for them to live a long time and to not be sick and die from pulmonary hypertension. And oftentimes, we will focus on that conversation, which is so important, hearing the patient say, you know what, I feel so much better that I’m on these two medicines, thank you so much, it’s really helping me, and I think we all celebrate that together with our patients, it’s what we want to hear, it means just as much to us, often, as it means to them, even if they don’t always realize that. But I also think that we’ve learned that while we want to celebrate the patient’s improvement, we also hold ourselves to really a higher standard of care, which is not just feeling better or walking further during a six-minute walk test, but achieving as close to normal heart function as possible. So a very common scenario, I would say, is the patient meets us for the first time, I know you have hundreds of patients like this that come to you, and they’re sick with pulmonary hypertension, and you start them on medication, and then they see you again, and they’re feeling better, and I think that’s a really important time frame. And it’s usually within that first few months, even, I would say, no more than three months to say, okay, these medicines have taken effect, that’s great, but let’s look at the heart with the echocardiogram and confirm that not only are you feeling better, but that it is as improved as we should expect it to be. And oftentimes, it’s improved somewhat, but we realize it’s not as good as we would want it to be. And so, while we celebrate the patients feeling better, we have to really keep going and be more progressive about it. And so, I use that echocardiogram, the most I would wait is three months after initially starting treatment.

Lana Melendres-Groves, MD:

I think that I often don’t even think of it that aggressively, so it’s really nice to hear you bring that up and say, potentially getting more frequent Echos than maybe I even would have could be to the benefit of our patient. And I know that we could truly talk about this for hours on end, but to make sure that everybody is able to stay with us through the entire broadcast, I guess I’ll have to bring us to a close. But just to say, thank you for your time and your insight, and hopefully we’ll be able to have time in person to catch up soon.

Anjali Vaidya, MD, FACC, FASE, FACP:

Thank you. And thank you Lana for taking the initiative on so many of these educational endeavors. It’s a huge contribution, and to everyone from the PAH initiative, thank you for having me.

Lana Melendres-Groves, MD:

Well, I want to thank Dr. Vaidya again for being here. She’s such a tremendous resource when it comes to understanding Echo, and she’s so committed to treating patients with PAH just as I am.

Now I’d like to move into our third and final section, which is called Learning More. I think all of us can say that we definitely have more to learn, no matter, it be about PAH or so many other aspects of our lives. But today, in terms of Echo, we continue to learn more and understand its importance. There was actually a recent study that took patients who were a Functional Class 2 patient, and again, I don’t want to overwhelm anybody who maybe wasn’t part of some of our prior broadcasts, but a Functional Class 2 patient is somebody that has some limitations when they’re trying to do their activities of daily living or exercising, but they’re still able to manage them. These patients were taken, and it was looked at to see the frequency of echocardiograms. What they found was that physicians who performed Echos every three months were able to better assess their patients’ disease status vs. those physicians who performed Echos every 7 to 12 months, indicating that potentially the more frequently we’re looking at the pictures of the heart through an Echo, the better we might be able to react to what our patients’ needs are. So, it’s key to finding a PAH specialist who’s right for you.

[on-screen text: PAH is a rare disease so not all cardiologists and pulmonologists have expertise in treating it. PAH experts have experience understanding Echos from patients with PAH. These specialists can use Echos to interpret how a treatment plan is impacting the right heart.] Now, as you saw today, you had a cardiologist join us who’s well versed in echocardiograms and PAH, and I am a pulmonologist who also has taken a tremendous interest in understanding Echos and treating patients with PAH. So, it’s less about what subspecialty they are and more about what their expertise is because not every specialist will understand Echos, nor will they understand PAH, so feel free to talk to them and ask them in terms of what they feel they’re comfortable doing, and if you don’t feel comfortable with it, we welcome you to take a look at the phassociation.org/patients/doctorswhotreatph/. This may give you an idea of physicians or providers in your community who feel that they have a good grasp of PAH and how to treat it.

So, in summary, monitoring the right heart is important in PAH. Changes in the heart are one of the first signs of worsening PAH. An Echo is a noninvasive way to look at the structure and function of the heart. The Echo currently is an important part of the risk assessment, and monitoring the right heart allows healthcare providers to be more proactive with treatment in an effort to prevent symptoms before they happen and help patients to lower their risk status. So, ask your healthcare provider about your heart and how it is changing over time.

Monitoring your RH is a crucial part of understanding the bigger picture of your PAH

Learn more about what your right heart health reveals about your PAH risk status.

PAH Life Expectancy & Risk Status

With PAH, narrowed blood vessels in the lungs cause blood flow to slow down and back up, similar to traffic during construction on a highway. This backup creates pressure, which strains the heart over time.

With PAH, narrowed blood vessels in the lungs cause blood flow to slow down and back up, similar to traffic during construction on a highway. This backup creates pressure, which strains the heart over time.  An important goal of treating PAH is to help the vessels in the lungs widen to improve blood flow, similarly to how traffic moves faster when more lanes are open. Because the blood flows more smoothly, there is less pressure and strain on the heart. Over time, with less strain on the heart, symptoms may also improve.

An important goal of treating PAH is to help the vessels in the lungs widen to improve blood flow, similarly to how traffic moves faster when more lanes are open. Because the blood flows more smoothly, there is less pressure and strain on the heart. Over time, with less strain on the heart, symptoms may also improve.